Editor's Choice

Mocking Medicine: Telling It Like It Is

Harriet Brunsdon

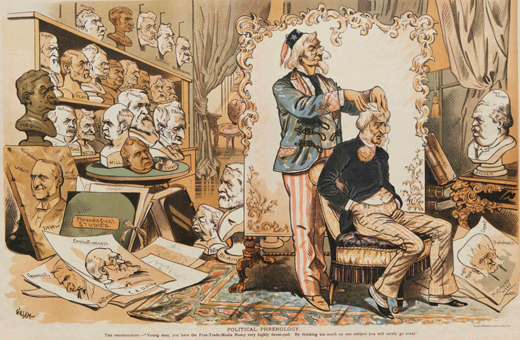

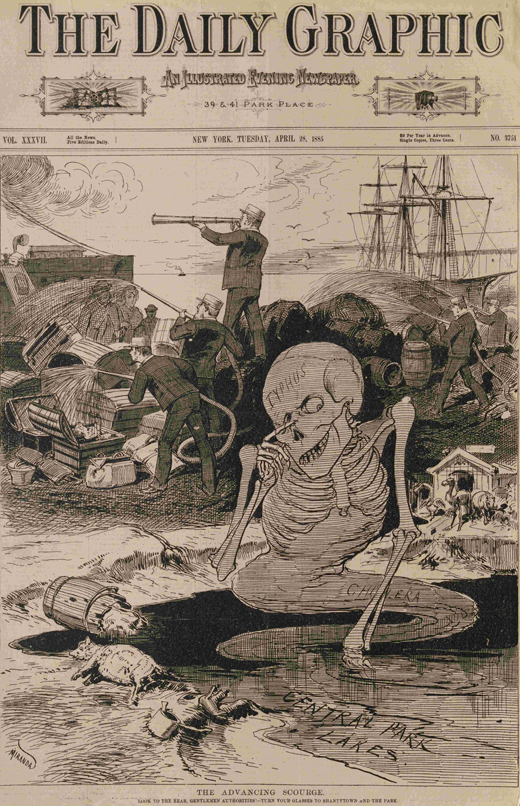

Popular Medicine contains some absolute treasures, and my personal favourite is a collection of satirical cartoons which appeared in the American magazines Puck, Judge and the Daily Graphic between 1873 and 1895.

Mocking the issues of the day is still one of society’s best antidotes to over-thinking, helplessness and frustration. It serves to put problems into perspective, and to say out loud what everyone is thinking but doesn’t dare to voice. In the late nineteenth century, the rift between ‘conventional’ and ‘alternative’ medicine made for some serious public debate and outspoken comments. ‘Quack’ doctors were being limited by restrictions passed by the American Medical Association, and laws against fraudulent advertising were starting to be put in place. Epidemics of yellow fever and malaria were rife, and trendy new medical techniques received publicity in good ways and bad. Medicine was in the news for all sorts of reasons, and was thus prime fodder for the cartoonists.

The levels of mockery varied enormously, the mildest being the ridicule of the quirky methods currently in vogue. Other cartoons exposed the exploitation of sick people by money-grabbing doctors and medical superstitions that brainwashed an ill-educated public. On a wider level, others used medicine as an illustration of public oppression in general, likening the US Senate to an invalid in need of urgent treatment, or the American people to plagued citizens oppressed by the disease and famine of bad government.

The levels of mockery varied enormously, the mildest being the ridicule of the quirky methods currently in vogue. Other cartoons exposed the exploitation of sick people by money-grabbing doctors and medical superstitions that brainwashed an ill-educated public. On a wider level, others used medicine as an illustration of public oppression in general, likening the US Senate to an invalid in need of urgent treatment, or the American people to plagued citizens oppressed by the disease and famine of bad government.

However, there is a macabre level of seriousness to some of the cartoons. The depiction of miasmic clouds of cholera approaching a town subtly implies that the people have only themselves to blame by their lack of sanitation and poor hygiene (the connection between sanitation and illness was a comparatively new discovery). Another shows the authorities desperately disinfecting items coming ashore off a ship, while a New York lake of rat- and rubbish-infested water teems with typhus behind them.

Somebody once said that a picture is worth a thousand words, and cartoons in particular can make a point like nothing else can. What other medium can simultaneously offend everybody and nobody, and make people both laugh and cry?

Medication: The Key to Marital Bliss?

Hayley High

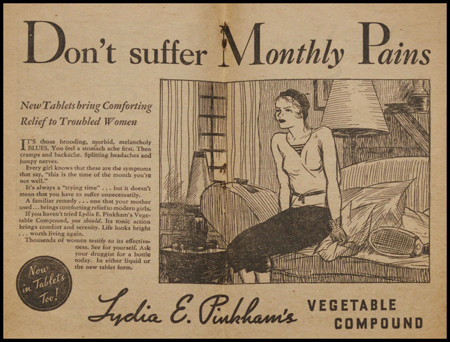

Over the past few years there has been increasing concern about the ‘over-medicated’ populations of the Western world with fears, for example, that humans will soon become resistant to existing antibiotics. One text entitled ‘Marriage Problems’, dating from the early twentieth century, did not share this concern and instead advised women to medicate themselves in order to achieve and maintain marital bliss.

This marriage guide informs women that four walls can make a house but it is their input which makes that house a home. It was the woman’s role to prepare the meals, keep the house tidy, raise healthy children and, above all, keep her husband happy. The pamphlet also instructs women that they need to look after their own health to ensure they are capable of achieving and excelling at all of the aforementioned tasks.

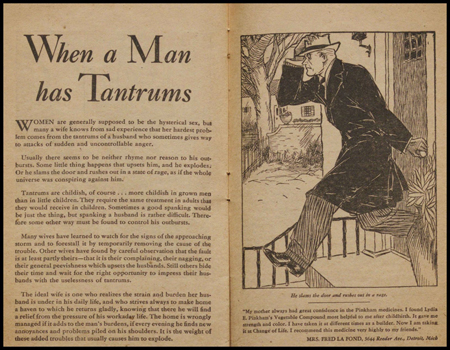

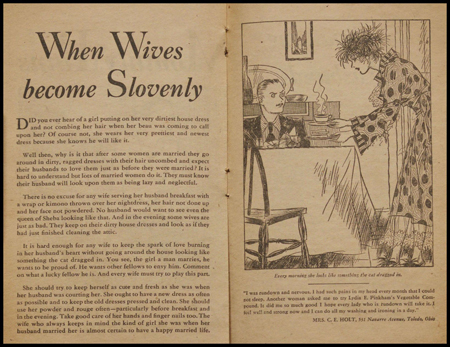

The text gives an overview of the ‘typical’ marriage; from its happy beginning through to the end of the honeymoon period and the inevitable descent into various periods of turbulence! Examples of these troubles include; what happens when the wife goes to work, when quarrels become brawls, gallivanting husbands, spendthrift wives and meddling mother-in-laws!! However, my two favourite examples are the pages on ‘When a man has tantrums’ and ‘When wives become slovenly’; showing what appears, at first glance, to be a refreshing sense of equality when it comes to who creates tensions within the household.

The former example explains that tantrums are more childish in grown men than in children but, while a good ‘spanking’ would be just the thing to correct such outbursts, chastising your husband in this way could prove difficult. Any sense of equal responsibility is thrown out of the window when the text advises; in response to her husband’s tantrums, the ideal wife should understand the strain their husband is under in his daily life and should make sure that coming home to a mismanaged house is not added to his list of burdens! The second example informs women that men do not want lazy, neglectful, wives that ‘look like something the cat dragged in’. It advises that ‘the wife who keeps in mind the kind of girl she was when her husband married her is almost certain to have a happy married life’. So much for ‘it takes two’ to make a marriage work.

From the information contained within this pamphlet, it would seem the advice of the day was that women should medicate themselves in order to both please their husbands and to maintain a pleasant and happy home. After all, ‘those dreadful headaches and backaches, that bearing-down feeling and [those] fits of dizziness…these things only a woman knows’ threaten both the female’s happiness and her husband’s patience!

Monstrous Museums and the 'Freak'

Monstrous Museums and the 'Freak'

Lindsay Gulliver

When I first began work on this resource, I spent several hours rifling through medical trade cards from the nineteenth century. While some featured optical illusions and hapless frogs, many focused on idealised illustrations of snowy homesteads, rosy-cheeked children and young love. However, this collection also harbours evidence of a darker side to medical science in a series of inventory catalogues.

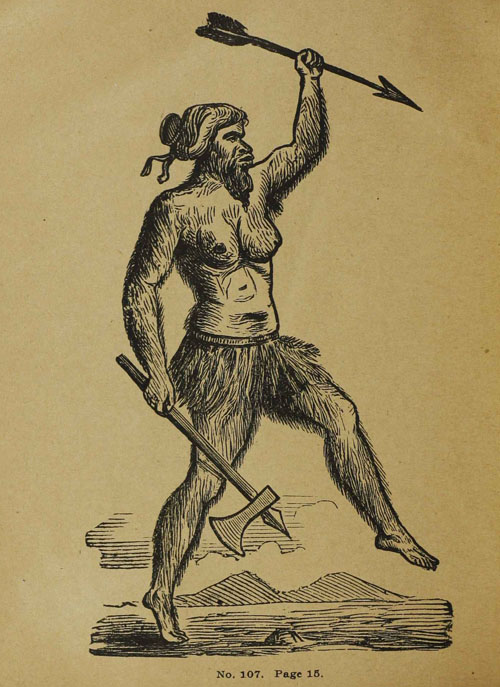

One particularly good example is the catalogue of Dr. Linn’s Museum of Anatomy. Institutions such as Dr. Linn’s didn’t stock the antiquities of ancient cities, but collections rather more bizarre. Curious customers marvelled at stereotypical representations of foreign races alongside diagrams and pickled remains depicting rare medical conditions. Museums aimed to dazzle punters with dioramas, paintings, relics, stuffed animals, waxworks and photographs. At this point in time, “otherness” was a great curiosity – many Americans would never travel to foreign lands, but ethnological exhibits displayed exotic “savages” and “cannibals” for only a dime. In the same display, one might find a model of a Sioux Indian ‘in his ware [sic] paint as he is about to throw his tomahawk’ and a Mongolian ‘with his barbed spear, ready to pursue his calling’, or compare the dissected heads of a “Negress”, a Patagonian and a New Zealander. Contemporary scientists were fascinated by the biology of different races, while displays of foreign tribes proved hugely entertaining to the masses.

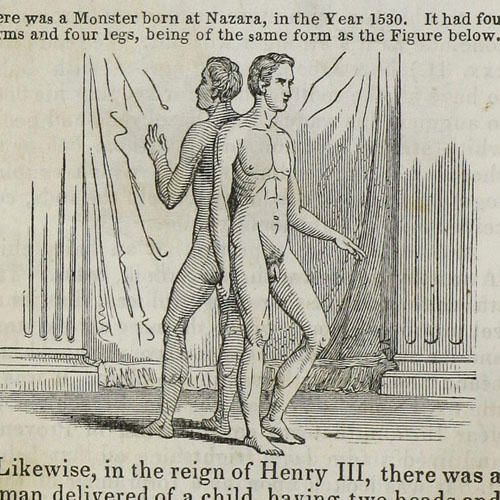

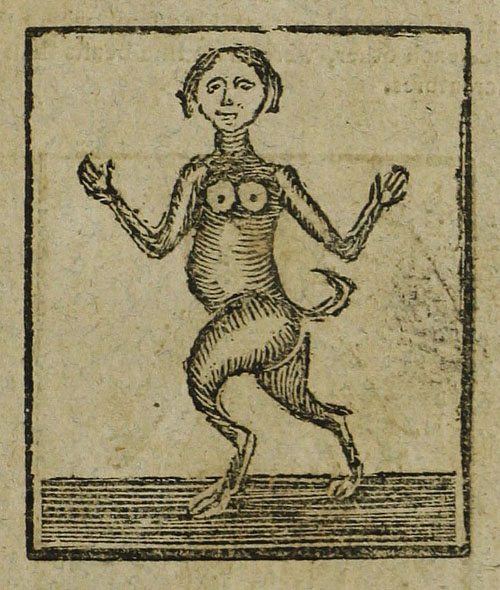

Though museums such as Dr. Linn’s advertised their educational credentials, most customers came to enjoy the spectacle rather than the science. Disease and deformity were fetishized for financial gain. Many such museums catered exclusively to men – women, after all, were prone to fainting spells and episodes of swooning! For the curious student, wax works of reproductive organs illustrated the human form in graphic detail, while the ruinous symptoms of venereal disease served as a warning against immorality. Monstrous births, preserved for posterity, were common; for example ‘a figure of a child completely developed in the womb with two mouths, two noses, three eyes, two ears and one head – the greatest curiosity in the world.’

Though museums such as Dr. Linn’s advertised their educational credentials, most customers came to enjoy the spectacle rather than the science. Disease and deformity were fetishized for financial gain. Many such museums catered exclusively to men – women, after all, were prone to fainting spells and episodes of swooning! For the curious student, wax works of reproductive organs illustrated the human form in graphic detail, while the ruinous symptoms of venereal disease served as a warning against immorality. Monstrous births, preserved for posterity, were common; for example ‘a figure of a child completely developed in the womb with two mouths, two noses, three eyes, two ears and one head – the greatest curiosity in the world.’

Common in Europe since the sixteenth century, the popularity and commercial potential of freak shows peaked in American in the nineteenth century. Celebrity circus owner, Phineas T. Barnum, popularised the entertainment. Alongside his famous museum of curiosities, he toured the length and breadth of the country with acts such as “General Tom Thumb” - a boy with dwarfism who he taught to sing, dance and perform impressions. His notorious advertising campaign asked, not ‘who’, but, ‘What is it?’

Hermaphrodites, conjoined twins, people born with gigantism, dwarfism or hypertrichosis (abnormal hair growth), were not people but attractions, stripped of their humanity for the crowd. To a contemporary reader, morbid museums and sideshows such as these seem cruel and exploitative, yet they could also be lucrative for the performers themselves; the original “Siamese” twins, Chang and Eng, were able to retire from the “freak” business, buy a farm and own several slaves.

Around the turn of the century, the appeal of such entertainments began to decline. After the First World War and its devastating impact upon the bodies of surviving soldiers, society became gradually more aware of disability. Catalogues such as these, while patently exploitative, stand as a testament to a time of curiosity before many medical conditions were truly understood.

Warts and All: The Medical Imagination

Amy Hubbard

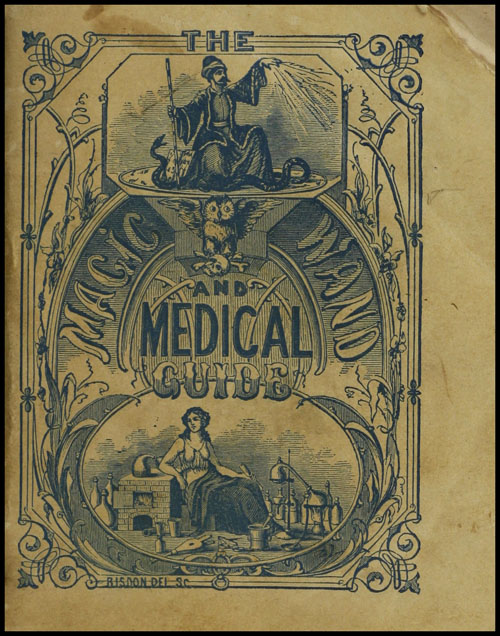

Having come across a number of captivatingly strange documents within the Popular Medicine collection I imagined that choosing a favourite would be impossible. However, one text in particular stuck in my mind for its sheer eccentricity and diversity – A. G. Levy’s ‘The Magic Wand and Medical Guide’, published in 1860. This text describes itself as “the most wonderful and entertaining book ever published” and, covering everything from sexual health, courtship, domestic recipes to the occult, alchemy and alien life, this is hard to contradict!

Having come across a number of captivatingly strange documents within the Popular Medicine collection I imagined that choosing a favourite would be impossible. However, one text in particular stuck in my mind for its sheer eccentricity and diversity – A. G. Levy’s ‘The Magic Wand and Medical Guide’, published in 1860. This text describes itself as “the most wonderful and entertaining book ever published” and, covering everything from sexual health, courtship, domestic recipes to the occult, alchemy and alien life, this is hard to contradict!

Levy’s text serves as a fascinating representation of the upheaval of medical culture during the nineteenth century, and of the influx of ideas both old and new that followed in the wake of orthodox medicine’s subversion. Levy dwells on older understandings of medicine which relied on the imagination as much as scientific rationality. Much of his advice seems to be predicated on wisdom endowed from oral tradition and folklore, teetering on the brink of reason and pretence. He advises on subjects such as infertility, for which women “must drink sage tea often and use pure salt. Plutarch says – Female mice will conceive only by licking salt”. For a clear complexion, he prescribes an ointment of “wild tansy, horse radish and sweet milk seed”, and to change eye colour one must “anoint the forehead with a solution from the ashes of hazel nut”.

To the modern reader, some of these old remedies that Levy terms “natural and celestial magic” seem ridiculous, but in the dubious nineteenth century medical climate the gravitas of old beliefs and methods was heightened. It is surprising how firmly such ideas took hold of the popular imagination. In my family, the understanding that spitting on a dock leaf and rubbing it on the skin will cure a nettle sting, or that honey and lemon or brown sugar and butter will soothe a sore throat, has been passed down through the generations. I’ve even inherited the knowledge that a cure for warts involves spitting on raw beef, placing it on the warts and then burying the beef in the garden! Whilst many of these ideas were clearly lacking in empirical evidence, based on this text’s popularity (being in its fourth American edition) their influence must have been considerable.

Interestingly there are two copies of this text in the Popular Medicine collection. In his preface, Levy warns of “charlatans” plagiarising his work due to his lack of copyright and it would seem that the “revised edition” from 1889 is proof of his fear. The 1889 edition bears no mention of A. G. Levy, and instead seems to have been appropriated by the Eureka Medical Sanitarium. Reflecting the increasing commercialisation of popular medicine, much of Levy’s text is replaced by passages advertising more up-to-date practices such as electro-magnetism and medicines specifically manufactured by the Eureka Medical Sanitarium. The role of the occult and folklore is used merely as a marketing ploy, relying on the fascination and weight of older traditions to sell the new products – “the Elixir of Life”, for example, promises the “restoration of youthful vigor and permanent cure of nervousness timidity” at the cost of one dollar (77).

Together these two editions provide a wonderful snapshot of America’s mutating medical culture in the nineteenth century, whilst also highlighting how the imagination had a powerful and influential role to play in its development.